A biweekly newsletter with public space news, resources, and opportunities.

A curated dispatch on all things public markets plus the latest announcements from the Market Cities Program.

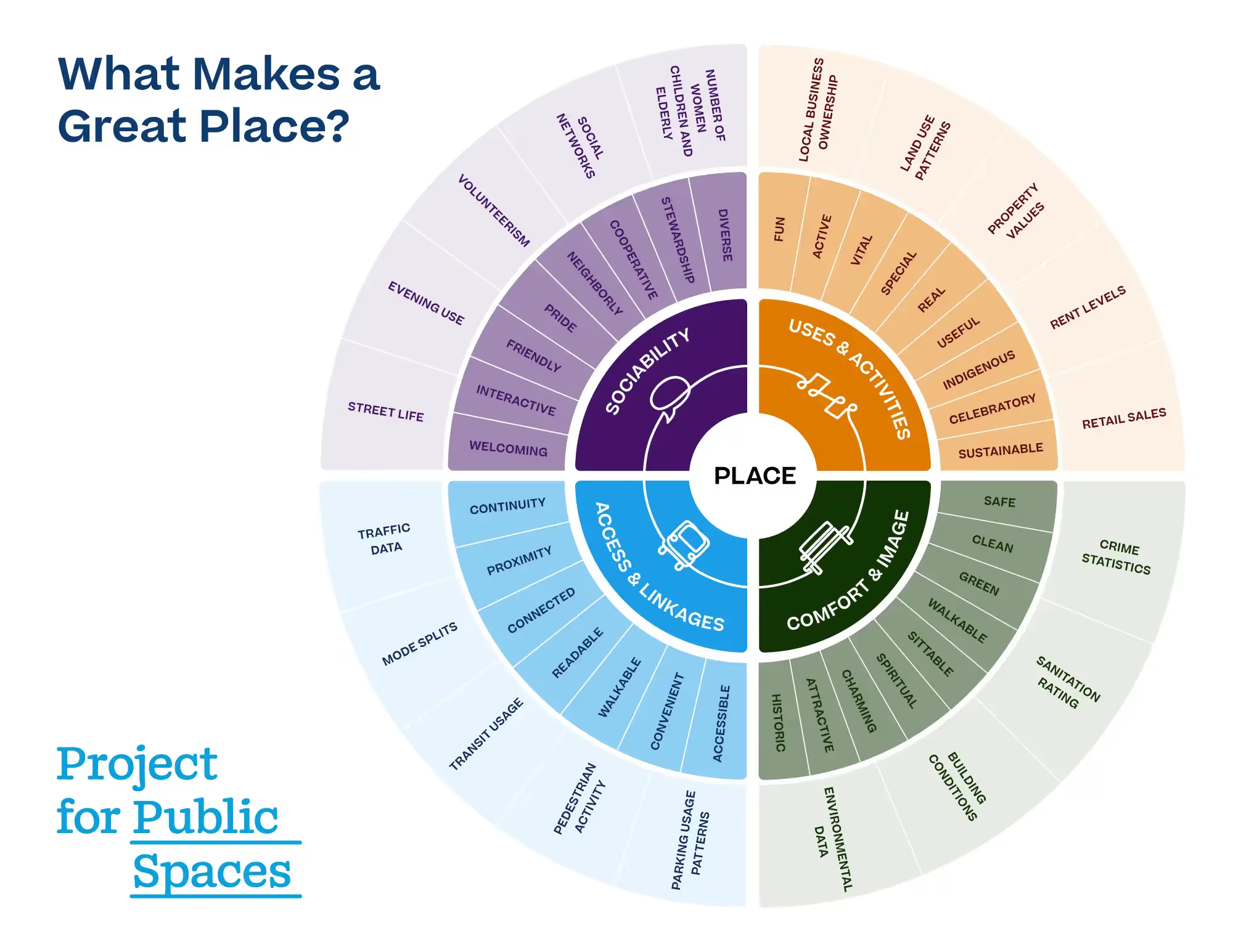

Editor's Note: This article is the first in a four-part series that explores the four segments of the Place Diagram, which answers the question, “What Makes a Great Place?” To learn how to implement and manage a placemaking project, register for our online training "Placemaking: Making it Happen" taking place in September. The early rate is available until July 20, 2023, at 11:59pm ET.

Since creating sociable, lively community places for all is the main goal of the placemaking movement, it makes sense that activity is seen as the beginning and end of the process—both the lens through which public spaces are created and an important measure of their success.

After all, imagining a public space is impossible without answering the question: “What can you do there?”

The Place Diagram, an important placemaking tool on which this article series is based, outlines the four elements that make a public space well used and well loved. This four-part series offers a deeper dive into each of these characteristics, beginning with the most fundamental building blocks of a great public space—uses and activities.

Uses and activities are a reflection of what's possible in a place, putting on display all of the aspirations, needs, and ideas that public spaces bring out of their visitors. Though less tangible than the other elements of great public spaces, uses and activities say the most about how well a place serves its community.

Read on for seven principles for cultivating a critical mass of use in public space with case studies from around North America.

To create a genuine local destination, you have to tune into what locals really want. That’s why amenities and programming have to be the result of community engagement, and in the best cases, they also draw on local resources, know-how, and materials.

In Mexico, a project called LAPIS (Lugares Amigables para la Primera Infancia), which focused on early childhood and youth placemaking, demonstrates how a combination of stakeholder outreach and local materials can spell success. When working on LAPIS, PlacemakingX Global Program Director and Fundación Placemaking México founder Guillermo Bernal focused on listening to the needs of local children as the starting point. Through drawing exercises and surveys based on the Place Diagram, members of the team were able to gather ideas from children and adapt them to various settings, from schools to streets to museums to natural conservation parks. This type of creative engagement fosters an inclusive environment in which community members can see their ideas guide the placemaking process.

After engaging with local community members, especially children under the age of five, Fundación Placemaking México created a wide variety of spaces: community centers, play plazas, schoolyards, spaces for cycling education, “naturalized patios” with nature-based designs, and more. “It’s not just about putting in a swing,” says Bernal. “It’s about creating spaces for different types of play as well as using local materials, supporting the local economy, promoting local culture, and more.” In this way, LAPIS’s core mission of supporting play is rooted incommunity resources and know-how, including the imagination of the local kids.

Project for Public Spaces builds a lot of its community engagement around the simple idea of identifying what people hope to do in a space. In the words of Project for Public Spaces Co-Executive Director Nate Storring, “We use the entire Place Diagram in our community engagement process but, usually, it all usually begins with uses and activities.” That’s why, after community engagement, a placemaking project moves forward with the development of a “program” for the public space, which defines what types of activities the place will be able to support. Storring notes, “We lay out a diagram of the uses in a public space, drawing bubbles to identify areas with a unique mix of activities.”

This diagram is paired with an activity matrix that organizes these activities over time, too. Mapping activities across the day, week, and year lays the groundwork for how a space will evolve and eventually informs the way that design and management are planned. Once you have a critical mass of these activities, Storring says, “You can get back into the design, asking ‘What kinds of design elements do we need? What kind of management elements do we need to bring that activity to life?’” In short, the whole of the placemaking process centers how people will use a space.

In the case of the LAPIS project, Fundación Placemaking México General Director Luciana Renner noted that different typologies of play (e.g. social games, fantasy games, challenging games) informed the way the spaces came together in communities across Mexico: Each LAPIS space was led with a simple, open-ended plan centering various games. This meant hiding places, stages, and other features that embodied the schoolchildren’s preferred activities.

To keep the initial momentum of such projects going, Bernal also believes that it’s crucial to designate a champion for a space and communicate with them. For the LAPIS spaces, partners from local agencies, nearby nonprofits, or adjoining institutions like museums and schools agreed to the task of maintaining the spaces built as part of the project. Once again, strong local use requires strong local support.

But this still leaves the question: How can public spaces support this program of uses? The rest of this article outlines some of the core strategies to make a public space that feels alive, buzzing with the activity of visitors.

Project for Public Spaces has long held the stance that form supports function. In other words, every design choice should be firmly connected to a demonstrated human need or aspiration for the space. While the design professions have come a long way from mid-century mistakes, public spaces still open today with patterns of paths designed to be seen from outer space or fancy materials chasing an abstract idea of “high quality” that fall apart in under a year.

The best designs start by answering the question, “What will people do here?” For example, the creation of NewBo City Market in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, was part of the city’s post-flood recovery process, which included among its priorities the need to address a lack of natural gathering places around town.

“Initially, it was about the social space,” notes Project for Public Spaces Co-Executive Director Kelly Verel, “and anchoring the neighborhood in public space.” Building on this foundation, NewBo project partners established a mix of uses to draw people in, blending traditional commercial activities with other supporting attractions.

In this case, not over-designing the common areas was crucial. A large, flexible lawn provides room for outdoor activities while the indoor part of the market strikes a balance between open space, permanent stalls, and a commercial kitchen. This approach has helped NewBo to host an array of activities for people of all ages, both connected to and independent from the market itself: cooking classes, live music, yoga, movie showings, and the finish lines of 5k races. In this way, NewBo has embraced flexibility and seasonality, and put uses and activities at the center of its role as “an anchor for the city.”

When it comes to how people use a space, or what types of activities are best, there are few wrong answers. In fact, one of the best ways to bring a place to come to life is to cultivate a dense and diverse mix of uses.

Project for Public Spaces calls this the Power of 10+. This is the simple idea that in order to thrive, an urban district, campus, or rural region needs 10 great destinations, each destination needs 10 distinct places within it, and each place needs 10 things to do. This critical mass of nested uses and activities helps to ensure that a city’s public realm is lively at all times of the day, week, and year.

Creating clusters of activities doesn't have to be complicated. In Project for Public Spaces’ “Placemaking: Making It Happen” training, Storring holds up American Veterans Memorial Pier in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, New York, as an example of a humble yet effective space, filled with simple attractions that are well-connected to the surrounding subway stations, bike paths, and dense residential areas. Benches, tables, waterfront views, and ample spots to rest make it an ideal place for many through primarily passive uses. People fishing populate the edges during the day, joined by picnickers or visitors to a local ice cream truck during evenings and weekends.

Storring notes that the pier’s array of amenities support it in becoming such a well-used gathering place: “Providing the fundamentals can make a public space an active platform for people’s everyday uses, whether that’s talking, eating, hanging out, or resting, even without a lot of management and programming.” Creating a place that supports multiple activities can start small by simply providing the basics that people need to bring their own uses to the space.

Ensuring that activities within a public space play off of one another is key to building up social interactions. William H. Whyte called this phenomenon triangulation. This has a lot to do with a varied mix of uses, as mentioned above, but also with their placement in relation to one another.

The recent renovation of the Shafter Library & Learning Center in Shafter, California, demonstrates how new and renovated facilities can play off of one another to create a larger, cohesive space. Project for Public Spaces worked with the Learning Center’s staff to expand the spaces and program offerings, especially for young people. Already a hub for kids after school, the Learning Center provides classes for adults, along with STEM classes and activities for younger visitors. To create more space, two new shipping container-based classrooms and a plaza were added, ushering in a new era for the center. These new destinations included a children’s reading room filled with kid-friendly furniture and art co-created with a local artist, as well as a multi-purpose classroom and a courtyard area.

According to Project for Public Spaces Director of Projects Elena Madison, staff at the Learning Center were then able to add many new classes because they now had the space, both indoors and out, to do so. One of the concepts was to use the outdoor plaza space for work that’s a little messier, like constructing things, building robotics, and painting. Already a place that was doing an impressive amount of programming in a very small facility, the expansion made room for even more ways to enjoy the Learning Center, each one playing off the others to make the space feel even more lively.

One secret to the success of the Learning Center is that it supports both passive and active uses right next to one another. While arts and sciences programming are certainly active examples, the Learning Center’s library is also a space where parents and older siblings often hang out. Ensuring that the Learning Center has a healthy mix of quiet reading areas and dynamic spaces designed for hands-on learning has helped it to flourish as a destination not only for kids, but also for their caretakers, and people of all ages.

Commercial uses can also add further reasons to visit a public space. Whether retail, dining, or temporary pop-ups, bringing businesses into a place can create another lively layer of social life when done right. The key is to make sure that the commercial activity does not dominate a space or crowd anyone out, and instead supports local entrepreneurs and reflects the cultures of local visitors.

In Birmingham, Alabama, Carmen Mays, the Founder and CEO of Elevators on 4th, saw an opportunity to revitalize the historic Fourth Avenue Business District. The district is a key marker of the history of Black entrepreneurship in Birmingham and is located next to the Civil Rights National Monument. Mays noticed that the area had fallen behind other commercial areas near downtown Birmingham, becoming underused by younger people. In large part due to the historic nature of the neighborhood, Mays saw a tendency toward “overly preservationist” practices, stating, “There is a balancing of what a significant portion of people view as sacred and how to make it more contemporary and enjoyable.” She went on to ask herself, in a place so charged with history, “How can we balance commercialisation and commemoration without it being perverse?”

The answer Mays found was threefold: positive communication, demonstration, and programming.

Oftentimes, Mays found that the underuse of the district’s spaces stemmed from people not knowing what they can do in a space with a traumatic and racialized history. That’s why positive communication is the first step in taking back a sense of ownership of a space.

“Our communication either constricts or expands what people think about a space,” observes Mays. “We need to be framing it differently so that the first thing that greets them is not a bunch of signs telling them how to behave.” Keeping conversations open-ended, thinking about what is possible rather than what isn’t allowed, is the best way for a public space to reach its full potential.

Creating what Mays calls an “affirmative space” in and around the district also means opening up and demonstrating new activities, including entrepreneurial ones, and making use of existing amenities. Mays has held multiple pop-up events in the district, including a pop-up art gallery in 2019 and a pop-up bazaar in 2020. The latter was “very tactical,” without permits from the City, and improvised to use parking spaces to mark social distancing between vendors’ booths. With food trucks in a nearby parking lot, a DJ in the adjacent park, and strategic placement of booths along the sidewalk, people passing through were easily able to see the kind of activity that was possible along Fourth Avenue.

After these activations, what is left of Mays’ three-step approach to revitalizing a historic business district is more regular programming. Through her demonstrations, it's now clear what kinds of activities add new life to the district. Now, the City of Birmingham can improvise with this knowledge and support commercial and other activities in the district.

Commercial activity can be a core element of how a space comes to life. Merely opening a space up to entrepreneurs, artisans, restaurateurs, and local business owners can make a huge difference for the space, boosting foot traffic as well as the local economy. The key to adding commercial activity to a public space in a way that complements, rather than dominates, is to find balance with other activities and keep what's on offer accessible.

Seeding a space with active uses, in which visitors directly engage with organized activities, requires some elbow grease. While it does not always require a formal calendar of events, it does help to have people dedicated to making activities in a place happen. To start, Project for Public Spaces' Elena Madison outlines two approaches to managing activities and programming: building organizational capacity or branching out to find programming partners.

In the first, more active approach, you or your organization become the event organizer, developing and supporting a series of events. This is true in places like the Shafter Library & Learning Center, where staff trained in education have kept up a steady and intentional drumbeat of activities curated around what they feel is needed in the community.

The other approach is to partner with stakeholders and nearby institutions, becoming a venue for other entities to bring in the bulk of programs and events, even bringing some of their followers to build a critical mass. This partnership approach has been used successfully at the NewBo City Market, where Project for Public Spaces' Kelly Verel mentions that cooking demonstrations and commercial kitchen activities are run by a local community college. In situations like these, Verel recommends that markets should be considered part of a portfolio of places where cultural institutions show off their good work.

Activity is at the core of any great place, and it must always be the starting point for imagining or re-imagining a public space. It provides the basis for all the other elements of great public spaces: If there’s no reason to come to a public space, it doesn’t matter if you can get there or feel comfortable staying there, and the likelihood of social interactions evaporates.

At the end of the day, a well-loved public space integrates a wide variety of planned and unplanned uses that serve and are served by the local community. But it takes planning and ongoing management to make the most of these uses and activities by developing a program, getting organized, triangulating, and managing potential conflicts, like those between commerce and complicated histories.

The end result of these efforts is worth it: A public space alive with the ballet of human use speaks for itself.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Body Text Body Link

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Here is some highlighted text from the article.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

We are committed to access to quality content that advances the placemaking cause—and your support makes that possible. If this article informed, inspired, or helped you, please consider making a quick donation. Every contribution helps!

Project for Public Spaces is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization and your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.