A biweekly newsletter with public space news, resources, and opportunities.

A curated dispatch on all things public markets plus the latest announcements from the Market Cities Program.

When Hurricane Helene tore through Western North Carolina in September 2024, it didn’t just flood homes and streets—it exposed the deep fragility in how American communities are built to withstand crises. With rerouted rivers, crumbling roads, failing power grids, and displaced families, entire towns were shaken to their core. Damages soared to tens of billions of dollars.

Across the United States, the civic infrastructure that once held neighborhoods together—public gathering spaces, trusted local stewards, shared rituals—is eroding. As Robert Putnam warned in his book Bowling Alone, this unraveling of the social fabric leaves communities brittle in the face of disruption. And as sociologist Eric Klinenberg argues in Palaces for the People, it’s this very web of everyday connection—our social infrastructure—that fortifies us in moments of crisis.

I had recently been embedded in the region to support Thrive Asheville, a community think-and-do tank focused on convening, educating, and mobilizing action around issues like sustainable tourism and affordable housing. When the hurricane hit, Thrive—like many local organizations—pivoted quickly, first into emergency response, then into recovery and rebuilding.

This article pauses to reflect on the lessons that surfaced in the first six months of that recovery. Some communities were vulnerable because of their geography; others because of sprawl. But the places that recovered fastest shared one thing in common: people already knew how to gather, organize, and care for one another.

In Asheville, North Carolina, the storm exposed a simple truth: the city’s design ultimately shapes its resilience and response capabilities.

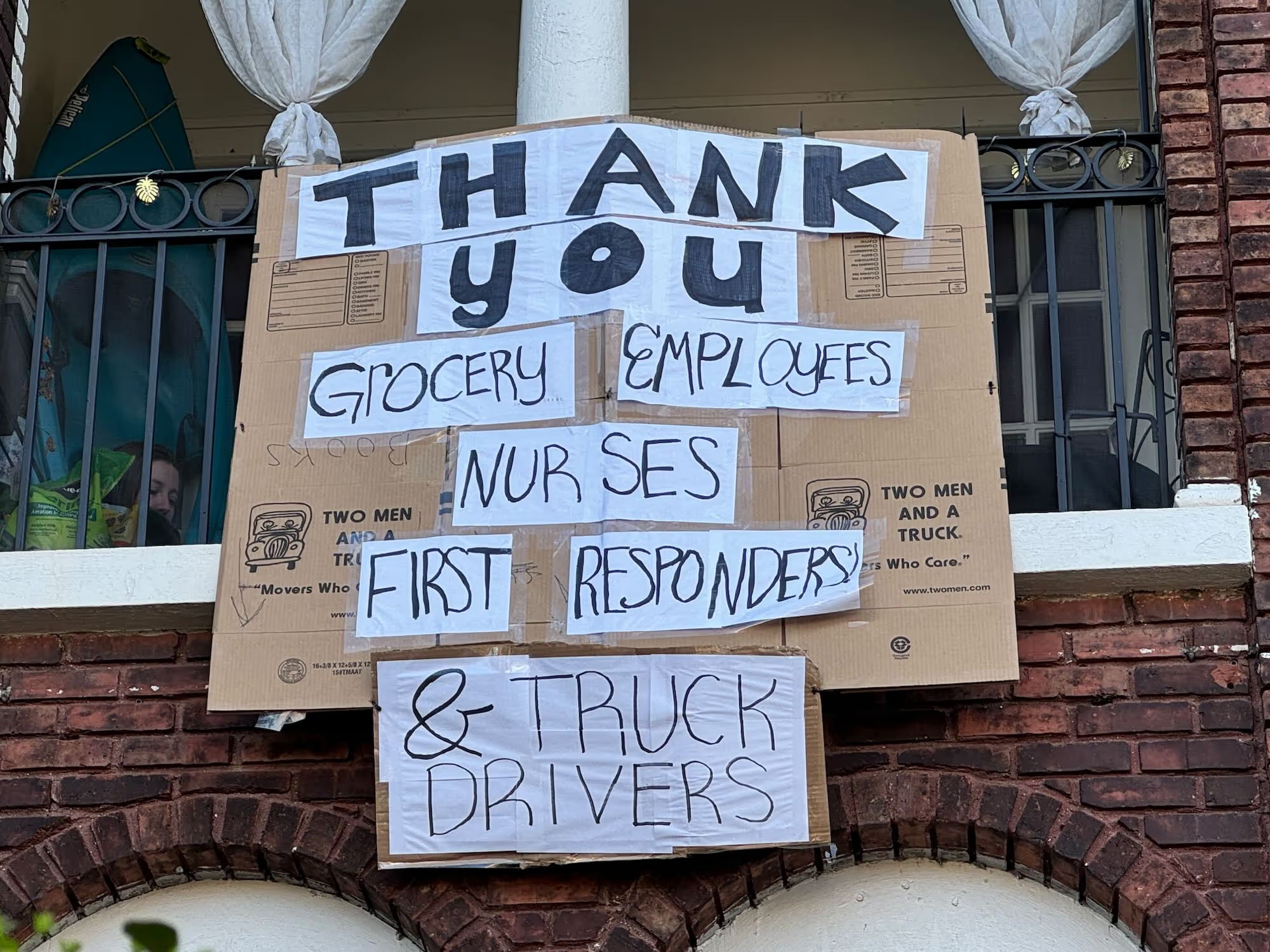

Walkable areas with human-scaled design and natural gathering points adapted quickly. Residents moved instinctively toward familiar places—churches, public markets, corner coffee shops, community centers—and those places transformed overnight into aid stations, supply depots, and hubs for checking in on neighbors. There was natural rhythm and flow as people knew where to go, who to seek, and how to help.

In contrast, where sprawl stretched across highways and disconnected lots, the story was different. With no clear civic heart or public square, people gathered wherever they could—behind warehouses, in the corners of big box parking lots. These makeshift aid sites worked for the most part, but they lacked comfort, coherence, and continuity. With no seating, shade, or sense of place, people came and went quickly, unsure of where to linger or who to follow.

Policies help shape what’s possible, but some needed reconsidering to meet the moment. Staff shortages meant the city temporarily suspended all permitted events, including the downtown farmers market—a vital food source and information hub—until public pressure brought it back. (This is a repeat of a pattern Project for Public Spaces observed during the pandemic.) Meanwhile, the main public lawn next to the city’s water distribution site remained barren, despite thousands visiting the surrounding area on a daily basis after the storm. These spaces could have supported not just logistics, but solidarity.

Place matters in crisis. What held together after the disaster were places built for people—spaces with visibility, orientation, and adaptability. Areas where people had to improvise and start from scratch faltered and took longer to recover.

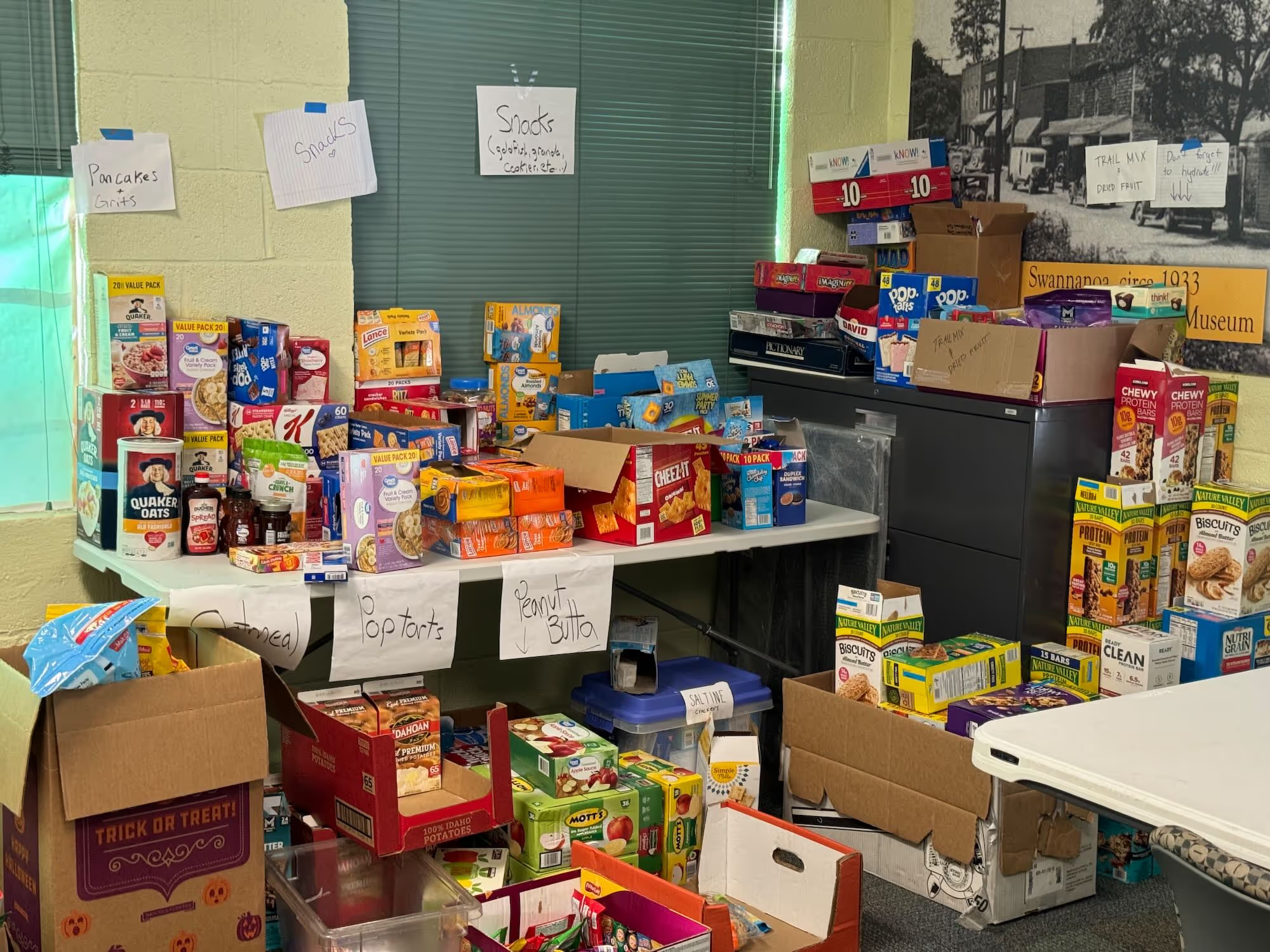

In addition to the white tents, clipboards, and official emergency operations we typically associate with disaster response, many of the most impactful recovery spaces emerged from lighter, quicker, cheaper community infrastructure at libraries, community centers, gardens, church halls, and businesses. These third places became Resilience Hubs for basic needs and platforms for trust, coordination, and local adaptation, where new forms of leadership and care emerged.

Here’s how it looked on the ground:

A Library Turns the Page: When county policy shut down public libraries, a board chair living nearby partnered with a local team to reopen one branch. Within hours, the space became a supply depot, charging station, and “restoration station” for emotional support.

A Gym With a Higher Calling: A Parks & Recreation employee who also pastored a congregation at a city facility had a standing rental agreement to use a community gym. That technicality allowed him to reopen the space—this time as a vital distribution site for food, hygiene kits, and more.

To DIY is to Live: Asheville had no potable water in the taps after the storm for 60 days. When water cisterns arrived in neighborhoods without nozzles, a volunteer from the Asheville Tool Library designed and 3D-printed custom spigots. Within 24 hours, the community had access to functioning water systems that would have otherwise sat unusable.

The Toilet Angels: With sewer systems offline, a group of residents began hauling pool water in buckets so their neighbors could flush their toilets. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was needed. And it worked!

Resilience is social infrastructure. These stories weren’t exceptions—they were real-life demonstrations of how community-based assets, when activated quickly and creatively, can complement formal emergency systems. They also revealed an opportunity for policy revision to support public buildings and third spaces with resilience-ready teams and protocols in place before disasters strike. That way, in these moments of need, the community knows who to hand a key to in order to get things up and running again.

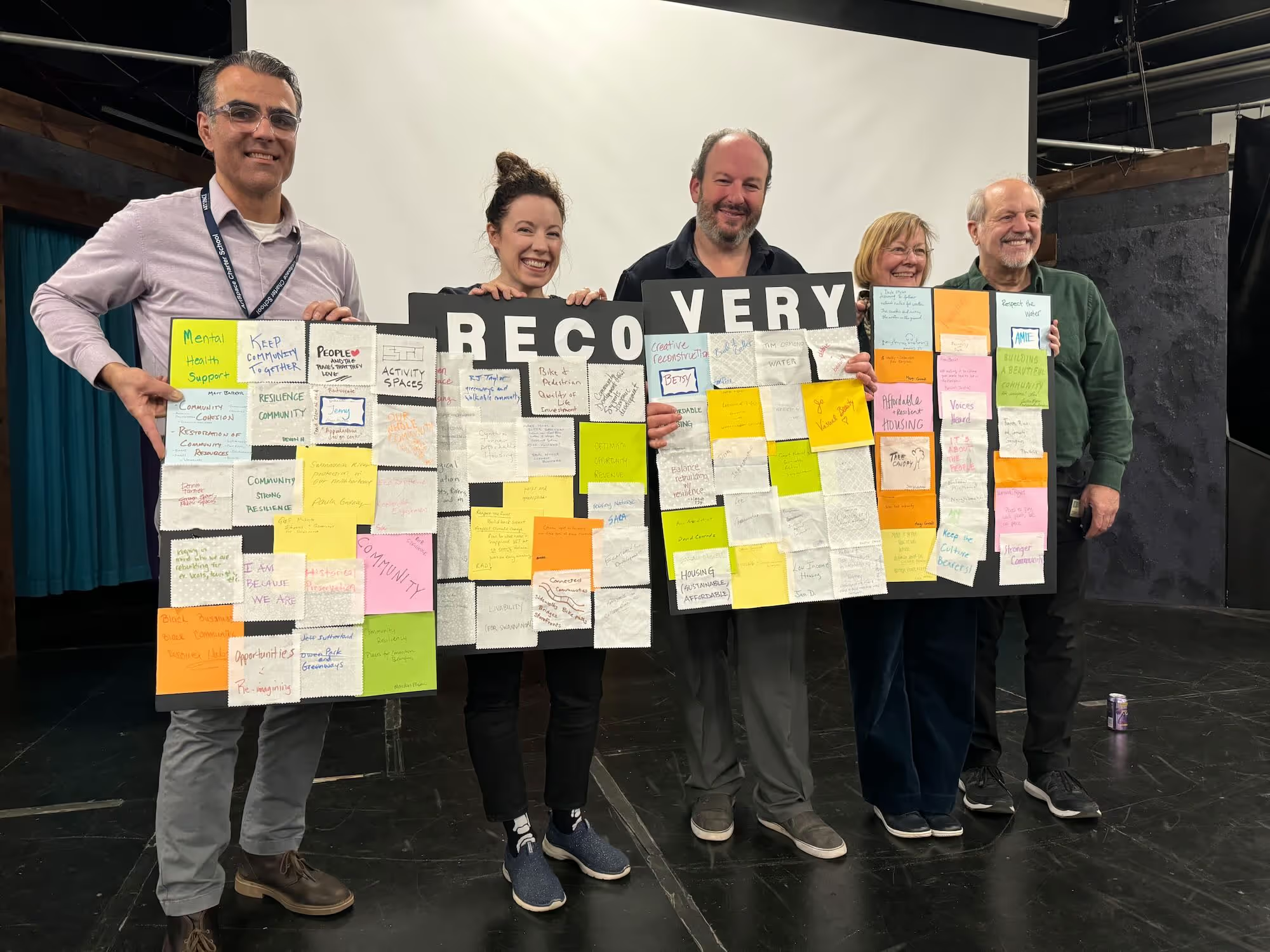

While Appalachia is known for its independent spirit, there was no shame in asking for help. In the weeks after Hurricane Helene, we turned to those who had faced disasters before—not for silver bullets, but for solidarity and insight. Thrive Asheville launched Lessons for the Recovery, a public learning series that brought together some of the most thoughtful voices in community-led disaster response. When spaces invite participation, remembrance, and renewal, they become engines of healing.

Each guest brought something essential—frameworks, stories, and provocations that reshaped how we thought about rebuilding, not as a checklist but as a deeply human process.

Dr. Ryan Reynolds of Gap Filler in Christchurch, New Zealand, brought play, provocation, and civic imagination. After earthquakes leveled much of his city’s core, his team deployed pop-up art, games, installations, and street furniture—not just to provide immediate relief, but to hint at what long-term recovery could become. He urged us to view impermanence not as a detour, but as a laboratory for human connection.

Angela Blanchard, who helped guide Houston’s recovery after Hurricane Harvey, reminded us that people are our greatest resource. She spoke of recovery as an emotional arc, not a timeline. People need space not just to rebuild, but to grieve, to connect, to create meaning. Her message was clear: our love for one another, our grace under pressure, and our desire to show up are what will carry us through.

Steven Bingler, a Principal at Concordia who helped shape New Orleans’ Unified Recovery Plan post-Katrina, centered the conversation on power and process. His message was blunt: people will decide what happens next, whether you invite them into the process or not. Top-down recovery plans fail when they leave communities on the sidelines. Steven showed us how to start small, engage authentically, and build outward from the specificity of place.

Together, these leaders reframed recovery not just as reconstruction—but as revelation. It’s a time to work through grief, hold space for memory, and make room for joy. Many of them came from New Orleans, a city fluent in the language of both loss and celebration—a place where mourning is followed by movement, where a dirge leads the way to a second line. They weren’t asking us to copy that spirit, but to find our own. Recovery, they reminded us, is cultural. It’s relational. It’s public.

Rebecca Solnit wrote that disasters often create a temporary “paradise built in hell”—a moment of extraordinary solidarity born from extraordinary loss. But that togetherness doesn’t have to be fleeting. We can build it into the everyday.

The question now is not if this will happen again. It’s where, when, and how ready we’ll be.

We need cities where people don’t just wait for help—they know where to go.

We need buildings that don’t lock down in crisis—but open up.

We need markets, parks, plazas, and porches designed not just for peacetime, but for any time.

In Asheville, we saw what’s possible. It was not a perfect response, but a human one that reflected a city where people carried the weight of collective care and first-responders weren’t just those in uniform; they were neighbors with keys, tools, and trust.

This summer, PlacemakingUS is taking the Lessons for the Recovery from Asheville on the road, hosting a series of workshops and learning exchanges across the country on how placemaking can strengthen both disaster recovery and everyday resilience.

Now, as disasters become more common and public systems show their limits, there’s a growing need for localized infrastructure that can respond quickly and equitably. Our aim with this tour isn’t to prescribe solutions—but to offer what we’ve learned. Through our Lessons for the Recovery tour, we’re building a learning community by sharing examples, tools, and frameworks that might help other communities shape their own response to disaster—rooted in their own context, culture, and capacity.

Placemaking can’t fix everything, but in Asheville it gave shape to uncertainty. It offered anchors in a sea of disruption. It reminded us that the places we build—when designed for gathering, comfort, and adaptability—become the scaffolding for recovery, not just the backdrop to it.

Resilience shouldn’t begin with the storm. It should begin with our places and the people in them.

Ryan Smolar is a Co-Director of PlacemakingUS and a placemaking consultant to Thrive Asheville. In 2021, Placemaking US’s Road Trip for the Recovery to over 70 cities helped mobilize over $10 million in American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding for local placemaking efforts. In 2023, its Train the Trainers Amtrak tour across 16 towns provided learning and sharing opportunities in towns built along another transportation imperative.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Body Text Body Link

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Here is some highlighted text from the article.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

We are committed to access to quality content that advances the placemaking cause—and your support makes that possible. If this article informed, inspired, or helped you, please consider making a quick donation. Every contribution helps!

Project for Public Spaces is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization and your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.