A biweekly newsletter with public space news, resources, and opportunities.

A curated dispatch on all things public markets plus the latest announcements from the Market Cities Program.

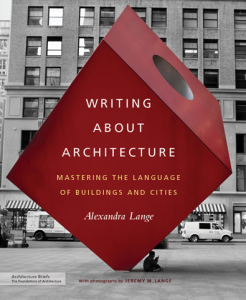

As Placemaking Blog readers already know, we're in the midst of launching a public conversation about the need for an Architecture of Place. In researching the current state of architectural criticism, we came across design critic Alexandra Lange's brand new book, Writing About Architecture, which serendipitously provides an in-depth look at how to write effectively about the very subject we were arguing needs to be written more effectively about!

Lange, who teaches criticism at New York University and the School of Visual Arts, has created a hybrid that is part anthology, part handbook. Writing About Architecture presents six essays by well-known critics, including Lewis Mumford, Michael Sorkin, and Jane Jacobs, using them to illustrate various aspects of successful and effective criticism. I recently had the opportunity to chat with the author via email about activist criticism, improving communication between citizens and designers, and how the democratization of media is opening up this field to new voices.

---------------------------------------------------

Brendan Crain: You devote a good deal of ink in Writing About Architecture to activist criticism, focusing (necessarily) on specific examples. Thinking more broadly, what would you say is the state of activist criticism today? Can you think of people who are doing a particularly good job with this kind of writing? And if there are any, what are some of the broader goals of contemporary activist design criticism?

Alexandra Lange: In the last chapter of my book I discuss Jane Jacobs, and how she might have reacted to the Atlantic Yards project. I think it needed a Jane Jacobs to stop it -- an advocate as eloquent about the costs, and the alternatives, as those seductive Gehry renderings -- and for whatever reason, one did not appear. But the activist spirit was by no means dead. It just got diffused into activist non-profits and activist blogs and activist essays. The diffused media landscape made it easier to follow the saga week by week, but perhaps made it harder for any one person to become the voice.

Activist criticism now is less likely to be on the pages of a major media outlet and more likely to be on a purpose-built blog. Jane Jacobs and Michael Sorkin had the Village Voice; today, I think of Aaron Naparstek and Streetsblog, which he founded but has now become a larger, multi-writer entity. He built his own platform for what the New York Times would not cover. That's incredibly exciting but also potentially limiting -- what if you have activist thoughts about other topics? Preservation is another area where I think critics can be effective, but I wouldn't want to write about modernist preservation all the time.

In terms of broader goals, I can think of three areas that seem to attract activism: public space (like PPS), preservation (like DOCOMOMO, Landmarks West!) and transportation (Transportation Alternatives, Streetsblog). But more people get their news about the city from places like Curbed and other real estate blogs, and I am still always hoping that those sites will get more critical, and put their readership to use. It isn't really in their personality profile, but I'm an optimist.

BC: That raises the question of why, at a time when architecture is purportedly paying more attention to social issues, the audience for writing about it seems to be shrinking, with the "death of architecture criticism" meme making the blog-rounds over the past few months. Groups that are particularly well-organized online--bicycling advocates, urban gardeners, transportation wonks, and even real estate gawkers--seem to dominate the conversation about cities. Discussions about architecture seem much more insular. How might the conversation about the built environment be opened up to appeal to a wider audience?

AL: I'm not sure I think the "death of architecture criticism" meme is real. I am sad when publications that have longstanding critic positions decide they don't need them anymore, but I wonder if the real story isn't architecture criticism exploring the new media landscape. TV criticism went through a tremendous transition, embracing the recap, rejecting the recap, making a case for itself as the central cultural critique of our day. It could be amazing if architecture criticism made a similar transition and came out stronger.

For that to happen, I think criticism needs to take more forms: not just appear in the culture section, but in news and opinion; appear on Twitter, in conversations with other fields; point out how it is central to questions of development, and environmentalism, and even television, that people are already engaged with. Readers need to recognize that it doesn't have a single personality. Unfortunately, the first people critics need to convince are the editors, and I know from experience that can be tough.

BC: In addition to diversifying the ways in which critical writing is being disseminated, does the scope of what what's being written about need to widen? In the book, you've included "You Have to Pay for the Public Life," an essay by Charles Moore that contrasts architectural with social monumentality. You note that, by Moore's definition, a place as simple and unadorned as a meadow can be considered monument if that meadow resonates with the surrounding communities -- "people make monuments." Do you think writing about more ordinary elements of the city could be helpful in broadening the audience for criticism?

AL: Moore's essay is one of my all time favorites, and I constantly refer to it in my thinking about public space and the way we make cities. 'Who is paying' and 'How are we paying' are questions relevant to almost any public space. In that chapter I even review, in a sense, the Urban Meadow in my Brooklyn neighborhood as a monument. So yes, I do think critics need to widen their scope, but I also think people need to notice that they've already done that, and have been doing it. Justin Davidson has a piece in this week's New York magazine about Times Square, and he's written about it at least one other time. Michael Kimmelman is making the architects mad by writing about planning and not architecture for the Times. Karrie Jacobs has been doing this all along. There was a tendency to starchitecture criticism, but it wasn't forever and it wasn't everyone.

BC: Due to the technological changes that you spoke of earlier, it's easy now for anyone with an interest in architecture and design to participate in the public discussion about these topics. Blogging and tweeting are to media, in a way, what "Lighter, Quicker, Cheaper" interventions are to design. In the book, you refer to Jane Jacobs' Death and Life of Great American Cities as "a primary document for a ground-up, deinstitutionalized form of architectural criticism." Are there other books, essays, blogs, etc. that you think are particularly instructive for people who, like Jacobs, aren't trained as designers or architects, but who want to write about how design affects their communities?

AL: I like the approach Alissa Walker takes on her own blog, Gelatobaby, as well in her freelance work (she now has a column at LA Weekly). I like the kind of events the Design Trust for Public Space organizes, creating social interactions in unusual parts of the city. I think Kevin Lynch's Image of the City is well worth reading, even though it is dated, because his mental mapping project, and the five elements of the city he identifies (path, edge, district, node, landmark), remain useful in trying to figure out what's missing. If you want to read more Lewis Mumford, I recommend the collection From the Ground Up, which has a lot about cars, housing and streets. I just read an essay on architecture and urban development in Kazakhstan by Andrew Kovacs, soon to be published in PIDGIN, that I found fascinating. Sometimes just reading an account of what it is like to walk around in a strange place is enough, and that's a great place for the non-designer to start. Get out the AIA Guide and go explore.

BC: Getting out and observing how a place works is something we highly recommend! But sometimes people can sense things intuitively about a place that they may not be able to articulate in a way that design professionals respond to. We conducted one of our How to Turn a Place Around training workshops at the PPS offices in New York last week, and one of the attendees said that she was participating because she would like "for designers to think more like citizens, and for citizens to think more like designers." You've included a bunch of great exercises in Writing About Architecture to help readers put lessons learned from the various essays into action. Can you think of one or two exercises that could help citizens to communicate their concerns more effectively to designers--and vice versa?

AL: I think for the non-designer, getting specific is really helpful. Achieving a higher level of noticing. Do you always trip on that step? Why do you take the stairs rather than the ramp? Is it just too hot in the park? Think about the height, the materials, the lighting level, the plants and try to figure out what it is that isn't working. No one likes to hear, "I just don't like it..." and I think making the problem as concrete as you can helps designers to hear you. Also, if you are in a place that isn't working, try to think of a similar one that you do like. What does that one have that this one doesn't? Compare and contrast is really effective.

As for the designers, I'm with the anti-archispeak contingent. Architects have to get specific too, and not talk about landscape elements rather than plants, etc. It is a kind of shorthand, but it is off-putting. More important, though, is to discuss the narrative of a project: why you chose this material rather than that, how it is supposed to make citizens (not users!) feel and act, what's the point. Everyone wants places that work, but there are so many different ways to get there.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Body Text Body Link

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Here is some highlighted text from the article.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

We are committed to access to quality content that advances the placemaking cause—and your support makes that possible. If this article informed, inspired, or helped you, please consider making a quick donation. Every contribution helps!

Project for Public Spaces is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization and your donation is tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law.