A biweekly newsletter with public space news, resources, and opportunities.

A curated dispatch on all things public markets plus the latest announcements from the Market Cities Program.

"Everyone has the right to live in a great place. More importantly, everyone has the right to contribute to making the place where they already live great." -Fred Kent, President, Project for Public Spaces

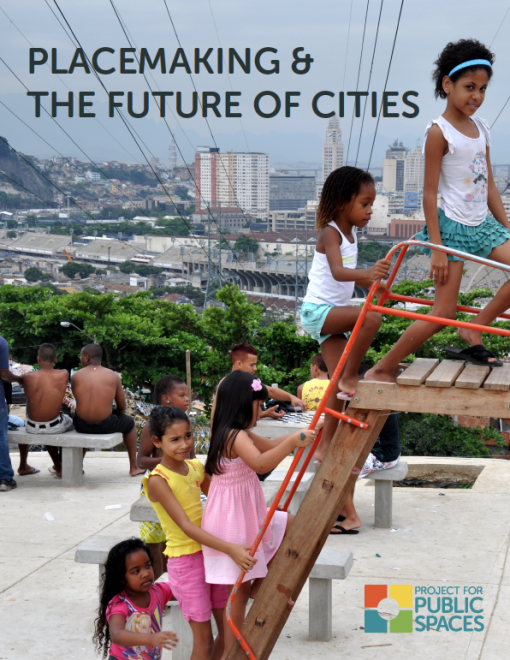

Placemaking can bring people together and create a sense of shared ownership of a city and its public spaces. Through Placemaking, community places not only become more active and useful for the people who help to create them, they can become more welcoming to people of all ages, abilities, income levels and backgrounds.

Since public spaces can both reflect and shape the communities they serve, they become incredibly meaningful places for people working to create more equitable cities. Many underserved communities have been systematically excluded from the prosperity and vibrancy that their city continues to generate for its wealthier residents. When neighbors come together to improve their public spaces, results can be tangible and immediate, and this process itself amplifies the sense of inclusion that great places can generate.

These benefits are often obscured in public debates surrounding Placemaking. Critics have voiced concerns, again and again, that Placemaking provides amenities that are geared toward a specific demographic—that its aim is to make "less desirable" areas more aesthetically palatable, and that it works to accelerate (or even initiate) gentrification by increasing property values and driving long-term residents out of their neighborhoods. Because of such fears, which urban critic Matt Yglesias has termed “gentrificationphobia,” neighbors often resist improvements to the public realm, from the installation of bike lanes to the development of long-vacant properties.

“It's not always that neighbors feel new development will make the area worse,” writes Yglesias, “sometimes they oppose new development because it will make the area better. [While concerns about people being priced out are not] crazy, it is crazy that this is the kind of thing people need to worry about in urban politics. 'Your policies will improve quality of life in my community' should never be a complaint about a policy initiative."

Here we can see the fundamental misunderstanding that has led to so much of the concern around Placemaking today. A bike lane is not Placemaking; neither is a market, a hand-painted crosswalk, public art, a parklet, or a new development. Placemaking is not the end product, but a means to an end. It is the process by which a community defines its own priorities. This is something that government officials and self-proclaimed Placemakers ignore at their own peril.

This is why the involvement of all residents is vital for creating great places. Placemaking offers a unique opportunity to bring people of different backgrounds together to work collaboratively on a common goal: a shared public space. When local officials, developers, or any other siloed group prescribe improvements to a place without working with the community, no matter how noble those groups’ intentions may be, it often alienates locals, provokes fears of gentrification, and increases the feeling and experience of exclusion. This kind of project-led or design-led development ignores the primary function of Placemaking--human connection.

In their report Places in the Making, an MIT research team led by Susan Silberberg highlights the importance of Placemaking in creating an equitable society:

The social goals of building social capital, increasing civic engagement and advocating for the right to the city are as central to contemporary Placemaking as are the creation of beautiful parks and vibrant squares. Leading Placemakers around the country have known this for some time, and have been infusing their projects with meaningful community process, building broad consensus, creating financing mechanisms that bring unexpected collaborators to the table, and other strategies demonstrated in the case studies presented in this paper. The canon of Placemaking’s past taught us valuable lessons about how to design great public places while planting the seeds for a robust understanding of how everyday places, third places, foster civic connections and build social capital. The Placemakers of tomorrow will build on this legacy by teaching us valuable lessons about how the making process builds and nurtures community.

Discussions about equity in communities are inseparable from discussions about creating more diversity within communities. As opportunities for social friction have declined, suspicion between different groups of people has risen, further reinforcing patterns of segregation and isolation. But since people read their city by the reflections of local communities that they see in the public realm, our parks, plazas, streets, and squares offer us a tool for shifting local culture. Creating more diverse places is important, but the way to do this is not to focus directly on diversity; diversity itself is a goal, not a tool. To get there, we must develop mechanisms and processes that make people of all backgrounds feel welcome, as co-creators, in the making of places—in essence, we need a more place-centered form of governance.

The Right to the City is a right to create, to participate, to be represented--it is the right to see oneself reflected in the place they live. It is a right that people understand intuitively, even (or especially) when they live in places where this right has been restricted. We see this in the graffiti that has been painted on the walls of cities in conflict, we hear it at so many of the protests that have spilled out of public squares in recent years. Acts of civil disobedience are demands for the right to the city; they show that people want to be involved in the decisions that impact their communities. And this right to participate has been shown to be directly related to human happiness and well-being. Placemaking, by solidifying the links between people and their shared places, can enable us to stitch our cities back together. When we feel connected to a space, we are more likely to experience our connection to others within that space.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Body Text Body Link

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

Here is some highlighted text from the article.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.

Headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, figures, images, and figure captions can all be styled after a class is added to the rich text element using the "When inside of" nested selector system.